UEL 2017 Inglês - Questões

Abrir Opções Avançadas

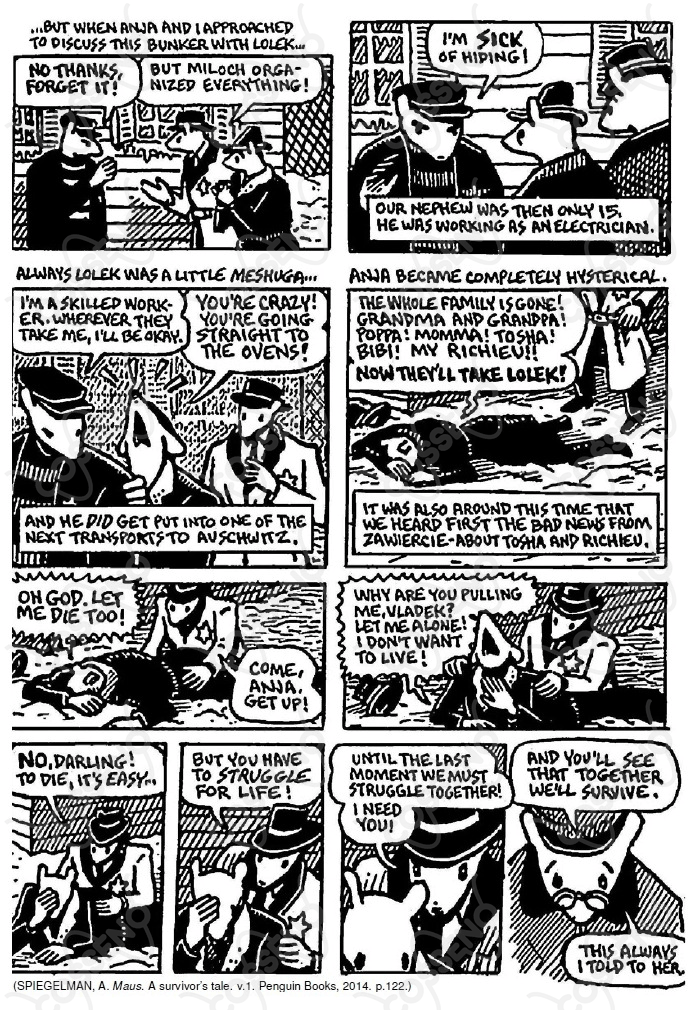

Leia o texto a seguir.

(SPIEGELMAN, A. Maus. A survivor’s tale. v.1. Penguin Books, 2014. p.122.)

Considerando os elementos verbais e não verbais do texto, assinale a alternativa correta.

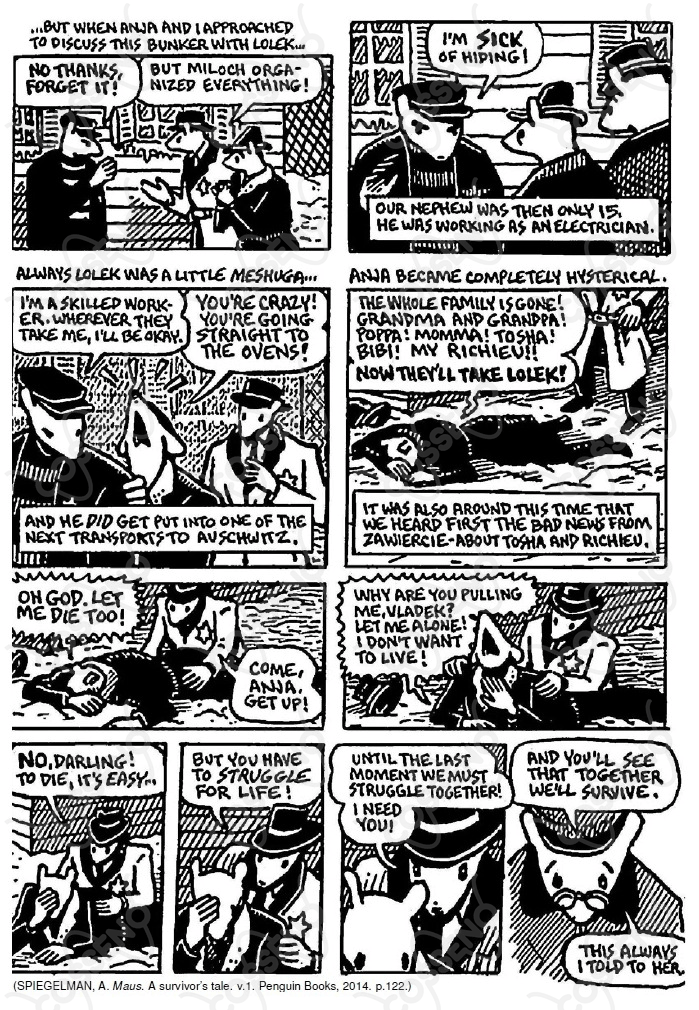

Leia o texto a seguir.

(SPIEGELMAN, A. Maus. A survivor’s tale. v.1. Penguin Books, 2014. p.122.)

Em relação ao uso da linguagem verbal no texto, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I) A posição da palavra “always” em “Always Lolek was a little Meshuga” e “This always I told her” contribui para a caracterização da personagem Vladek como um estrangeiro falante de inglês.

II) O uso de “did” em “And he did get put into one of the next transports” intensifica a ação narrada, ao mesmo tempo em que confirma a previsão de Anja em “You’re going straight to the ovens!”.

III) Em “To die, it’s easy... But you have to struggle for life!”, a posição do verbo “die” na frase tem a função de acrescentar ênfase.

IV) O uso da expressão “be sick of” em “I’m sick of hiding” descreve a condição física da personagem Lolek, resultante da precariedade dos abrigos.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Leia o texto a seguir.

When the marketing team behind Me Before You came up with the hashtag #LiveBoldly to promote this story of a young disabled man considering assisted dying, they could scarcely have predicted that it would be used to expose the movie’s problematic message. “Do you really want us to #LiveBoldly or do you just want us to #diequickly?” asked one commenter during a Twitter Q&A session last week with the film’s star, Sam Claflin.

He plays Will, a wealthy former playboy who becomes involved with Lou (Emilia Clarke), a rather eccentric girl. The film portrays the blossoming romance between these two apparently mismatched souls. Lou has full use of her body. Will has been quadriplegic since a road accident several years earlier. Before Lou became his carer, Will decided he wanted to kill himself. The full meaning of the name “Will” becomes clear only after he dies and leaves Lou enough money, he says, for her to swap her timid life for adventure. The problem, $\underline{\text{according to}}$ activists, is this motto applies in this context only to the able-bodied – and comes $\underline{\text{at the cost of}}$ a disabled man’s life. “We have so few opportunities in the media to explore disability”, $\underline{\text{says the actor}}$ and activist Liz Carr, who participated in the protest. “But there is a disproportionate number of stories which relate to the ‘$\underline{\text{problem}}$’ of disability being solved by death. Television and film seem to love those individuals who want to die. They’re less keen to cover the rest of us who might want to live but are struggling to get the health and social care resources to do so.” The screenplay offers one preventative measure to the charge that it is speaking for all disabled people. “I get that this could be a good life”, says Will. “But it’s not my life. I can’t be the sort of man who accepts this.” Since Will is shown to be strong, determined and uncompromising, it seems clear that the “sort of man” who would put up with a paralyzed body and its demands could only be inferior to him. This problem could be tempered, if not solved, by the presence of just one disabled character to provide some contrast and show that suicide isn’t the only option. But there isn’t one. The film isolates Will entirely, stacking the odds so that the choice to take his own life is made to seem like the logical one. “When non-disabled people talk of suicide, they’re discouraged and offered prevention”, $\underline{\text{she says}}$. “Even though it’s legal, it’s not seen as desirable. When a disabled person talks of it, though, $\underline{\text{suddenly}}$ the conversation is overtaken with words like ‘choice’ and ‘autonomy’ and people are $\underline{\text{rushing}}$ to uphold these prized principles while talk of prevention and mental health support are rare. Will is not offered any psychiatric support. What kind of message is this that we’re giving disabled people and the non-disabled audiences?”

(GILBEY, R. I’m not a thing to be pitied’: the disability backlash against Me before You. The Guardian. 2 jun. 2016. Disponível em:

Assinale a alternativa que apresenta, corretamente, o principal objetivo do texto.

Leia o texto a seguir.

When the marketing team behind Me Before You came up with the hashtag #LiveBoldly to promote this story of a young disabled man considering assisted dying, they could scarcely have predicted that it would be used to expose the movie’s problematic message. “Do you really want us to #LiveBoldly or do you just want us to #diequickly?” asked one commenter during a Twitter Q&A session last week with the film’s star, Sam Claflin.

He plays Will, a wealthy former playboy who becomes involved with Lou (Emilia Clarke), a rather eccentric girl. The film portrays the blossoming romance between these two apparently mismatched souls. Lou has full use of her body. Will has been quadriplegic since a road accident several years earlier. Before Lou became his carer, Will decided he wanted to kill himself. The full meaning of the name “Will” becomes clear only after he dies and leaves Lou enough money, he says, for her to swap her timid life for adventure. The problem, $\underline{\text{according to}}$ activists, is this motto applies in this context only to the able-bodied – and comes $\underline{\text{at the cost of}}$ a disabled man’s life. “We have so few opportunities in the media to explore disability”, $\underline{\text{says the actor}}$ and activist Liz Carr, who participated in the protest. “But there is a disproportionate number of stories which relate to the ‘$\underline{\text{problem}}$’ of disability being solved by death. Television and film seem to love those individuals who want to die. They’re less keen to cover the rest of us who might want to live but are struggling to get the health and social care resources to do so.” The screenplay offers one preventative measure to the charge that it is speaking for all disabled people. “I get that this could be a good life”, says Will. “But it’s not my life. I can’t be the sort of man who accepts this.” Since Will is shown to be strong, determined and uncompromising, it seems clear that the “sort of man” who would put up with a paralyzed body and its demands could only be inferior to him. This problem could be tempered, if not solved, by the presence of just one disabled character to provide some contrast and show that suicide isn’t the only option. But there isn’t one. The film isolates Will entirely, stacking the odds so that the choice to take his own life is made to seem like the logical one. “When non-disabled people talk of suicide, they’re discouraged and offered prevention”, $\underline{\text{she says}}$. “Even though it’s legal, it’s not seen as desirable. When a disabled person talks of it, though, $\underline{\text{suddenly}}$ the conversation is overtaken with words like ‘choice’ and ‘autonomy’ and people are $\underline{\text{rushing}}$ to uphold these prized principles while talk of prevention and mental health support are rare. Will is not offered any psychiatric support. What kind of message is this that we’re giving disabled people and the non-disabled audiences?”

(GILBEY, R. I’m not a thing to be pitied’: the disability backlash against Me before You. The Guardian. 2 jun. 2016. Disponível em:

Assinale a alternativa que apresenta, corretamente, os argumentos oferecidos pelos ativistas e pelo filme em relação à polêmica levantada.

Leia o texto a seguir.

When the marketing team behind Me Before You came up with the hashtag #LiveBoldly to promote this story of a young disabled man considering assisted dying, they could scarcely have predicted that it would be used to expose the movie’s problematic message. “Do you really want us to #LiveBoldly or do you just want us to #diequickly?” asked one commenter during a Twitter Q&A session last week with the film’s star, Sam Claflin.

He plays Will, a wealthy former playboy who becomes involved with Lou (Emilia Clarke), a rather eccentric girl. The film portrays the blossoming romance between these two apparently mismatched souls. Lou has full use of her body. Will has been quadriplegic since a road accident several years earlier. Before Lou became his carer, Will decided he wanted to kill himself. The full meaning of the name “Will” becomes clear only after he dies and leaves Lou enough money, he says, for her to swap her timid life for adventure. The problem, $\underline{\text{according to}}$ activists, is this motto applies in this context only to the able-bodied – and comes $\underline{\text{at the cost of}}$ a disabled man’s life. “We have so few opportunities in the media to explore disability”, $\underline{\text{says the actor}}$ and activist Liz Carr, who participated in the protest. “But there is a disproportionate number of stories which relate to the ‘$\underline{\text{problem}}$’ of disability being solved by death. Television and film seem to love those individuals who want to die. They’re less keen to cover the rest of us who might want to live but are struggling to get the health and social care resources to do so.” The screenplay offers one preventative measure to the charge that it is speaking for all disabled people. “I get that this could be a good life”, says Will. “But it’s not my life. I can’t be the sort of man who accepts this.” Since Will is shown to be strong, determined and uncompromising, it seems clear that the “sort of man” who would put up with a paralyzed body and its demands could only be inferior to him. This problem could be tempered, if not solved, by the presence of just one disabled character to provide some contrast and show that suicide isn’t the only option. But there isn’t one. The film isolates Will entirely, stacking the odds so that the choice to take his own life is made to seem like the logical one. “When non-disabled people talk of suicide, they’re discouraged and offered prevention”, $\underline{\text{she says}}$. “Even though it’s legal, it’s not seen as desirable. When a disabled person talks of it, though, $\underline{\text{suddenly}}$ the conversation is overtaken with words like ‘choice’ and ‘autonomy’ and people are $\underline{\text{rushing}}$ to uphold these prized principles while talk of prevention and mental health support are rare. Will is not offered any psychiatric support. What kind of message is this that we’re giving disabled people and the non-disabled audiences?”

(GILBEY, R. I’m not a thing to be pitied’: the disability backlash against Me before You. The Guardian. 2 jun. 2016. Disponível em:

Com base nas expressões sublinhadas no texto, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I) A palavra problem é usada com ironia, revelando a opinião do enunciador.

II) A utilização dos termos suddenly e rushing revela aspectos positivos acerca do suicídio assistido.

III) O uso da expressão at the cost of indica uma posição favorável do enunciador em relação à situação apresentada.

IV) Os termos according to, says the actor e she says foram empregados com o propósito de dar imparcialidade ao texto.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Carregando...